I've just had one of those mini-conversations which has be scratching my head, I asked a coworker about "return early" being part of the coding standard or not, as it was being discussed by other parties.

His response was an emphatic, slightly arrogant and touchily obtuse, "I have no time for anyone arguing for not returning early from a function you've discovered you should not be in".

I however don't take such a black and white view, I see the pro's and con's of both approaches, importantly not returning from a function can, and is part of, driving process flow conversations and it aids in picking out structure which can be encapsulated away. The result being that instead of instantly exiting and potentially leaving spaghetti code you can see a flow, see where branching is occurring and deal with it...

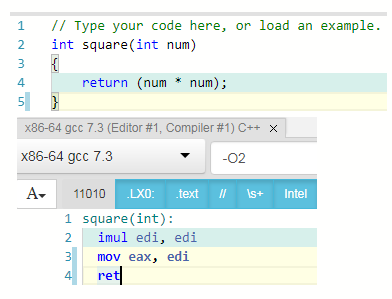

But, that said, it must be understood "returning early" is often seen as "faster", as the chap argued "I see no point being in a function you know you should already have left", so I took to compiler explorer... In a very trivial example:

Here we see a decision being made and either a return or the active code, easy to read, simple, trivial... But don't dismiss it too early, is it the neatest code?

Well, we could go for less lines of code which generates near identical assembly thus:

This is certainly less lines of C++ however, inverting the test is a little messy and could easily be overlooked in our code or in review, better might therefore be expanding the test to a true opposite:

One could argue the code is a little neater to read without the inverting, critically though it has made no difference to the assembly output, it's identical.

And it is identical in all three cases.

You could argue therefore that "returning early has no bearing on the functionality of the code", but that's too simplistic, because "not returning early" also has no bearing on the functionality of the code. The test and action and operation has been worked out by the magic of the compiler for us to be the same.

So with equivalent operation and generation we need think about what returning from the function early did affect, well it made the code on the left longer, yes this is an affectation of our coding with braces, but it was longer. You could also see that there were two things to read and take in, the test was separate to the code and importantly for me the test and the actual functional code were on the same indentation horizontal alignment. Being on that same alignment makes your eye not think a decision has been made.

Putting the test and the action of that test into the inner bracing communicates clearly that a decision has been made and our code has branched.

And when that structure is apparent you can think about what not returning early has done, well it's literally braced around the stanza of code to run after the decision, that packet of code could be spun off into it's own function do you start to think about encapsulation. Of course you can think about the same thing after the return, but in my opinion having the content of the braces to work within is of benefit and most certainly does not afford any speed benefits.

Lets look at a more convoluted, but no less trivial example, a function to load a file in its entirety and return it as a known sized buffer... we'll start with a few common types:

#include <memory>

#include <cstdint>

#include <string>

#include <cstdio>

#include <optional>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

using byte = unsigned char;

using DataBlock = std::shared_ptr<byte>;

using Buffer = std::pair<uint32_t, DataBlock>;

using LoadResult = std::optional<Buffer>;

And we'll assume there's a function to get the file size, with stat...

const uint32_t GetFileSize(const std::string& p_Path)

{

uint32_t l_result(0);

struct stat l_FileStat;

if ( stat(p_Path.c_str(), &l_FileStat) == 0)

{

l_result = l_FileStat.st_size;

}

return l_result;

}

Now, this file is return path safe because I define the result as zero and always get to that return, I could have written it thus:

const uint32_t GetFileSizeOther(const std::string& p_Path)

{

struct stat l_FileStat;

if ( stat(p_Path.c_str(), &l_FileStat) != 0)

{

return 0;

}

return l_FileStat.st_size;

}

But I don't see the benefit, both returns generate an lvalue which is returned, except in the latter you have two code points to define the value, if anything I would argue you loose the ability to debug "l_result" from the first version, you can debug it before, during and after operating upon it... Where as the latter, you don't know the return value until the return, which results in the allocate and return. And again in both cases the assembly produced is identical.

So, the load function, how could it be written with returning as soon as you see a problem?... Well, how about this?

LoadResult LoadFileReturning(const std::string& p_Path)

{

LoadResult l_result;

if ( p_Path.empty() )

{

return l_result;

}

auto l_FileSize(GetFileSize(p_Path));

if ( l_FileSize == 0 )

{

return l_result;

}

FILE* l_file (fopen(p_Path.c_str(), "r+"));

if ( !l_file )

{

return l_result;

}

Buffer l_temp { l_FileSize, std::make_shared<byte>(l_FileSize) };

if ( !l_temp.second )

{

fclose(l_file);

return l_result;

}

auto l_ReadBytes(

fread(

l_temp.second.get(),

1,

l_FileSize,

l_file));

if ( l_ReadBytes != l_FileSize )

{

fclose(l_file);

return l_result;

}

l_result.emplace(l_temp);

fclose(l_file);

return l_result;

}

We have six, count them (orange highlights) different places where we return the result, as we test the parameters, check the file size and then open and read the file all before we get to the meat of the function which is to setup the return content after a successful read. We have three points where we must remember and maintain to close the file upon a problem (red highlights). This duplication of effort and dispersal of what could be critical operations (like remembering to close a file) throughout your code flow is a problem down the line.

I very much know I've forgotten and missed things like this, reducing the possible points of failure for your code is important and my personal preference to not return from a function early is one such methodology.

Besides the duplicated points of failure I also found the code to not be communicating well, its 44 lines of code, better communication comes from code thus:

LoadResult LoadFile(const std::string& p_Path)

{

LoadResult l_result;

if ( !p_Path.empty() )

{

auto l_FileSize(GetFileSize(p_Path));

if ( l_FileSize > 0 )

{

FILE* l_file (fopen(p_Path.c_str(), "r+"));

if ( l_file )

{

Buffer l_temp { l_FileSize, std::make_shared<byte>(l_FileSize) };

if ( l_temp.second )

{

auto l_ReadBytes(

fread(

l_temp.second.get(),

1,

l_FileSize,

l_file));

if ( l_ReadBytes == l_FileSize )

{

l_result.emplace(l_temp);

}

}

fclose(l_file);

}

}

}

return l_result;

}

This time we have 33 lines of code, we can see the stanzas of code indenting into the functionality, at each point we have the same decisions taking us back out to always return. When we've had a successful open of the file we have one (for all following decisions) place where it's closed and ultimately we can identify the success conditions easily.

I've heard this described as forward positive code, you look for success and always cope with failure, whilst the former is only coping with failure as it appears.

I prefer the latter, ultimately it comes down to a personal choice, some folks argue indenting like this is bad, I've yet to hear why if the compiled object code is the same, you are communicating so much more fluently and have less points of possible human error in the code to deal with and maintain.

From the latter we could pick out reused code and we can target logging or performance metrics more directly on specific stanzas within their local scopes. Instead of everything being against the left hand indent line.

Now, I will happily tell you it hasn't been a comfortable ride to my thoughts on this topic, I started programming on a tiny screen (40x20 characters - Atari ST Low Res GEM and when I moved to DOS having 80 character widths I felt spoiled. Now we have tracts of huge screen space, arguing you need to stay on the left is moot, you don't, use your screen, make your code communicate its meaning, use the indents.

And yes, before you ask, I was doing things this way long before I started to use Python.